The ancient Rabbis said: "Who are wise? Those who learn from every human being."

This Commentary post is long overdue. However, it is coming at just the right time, really, as it deals with cycles. Judaism is oriented in several cycles, each of which complements the others, and adds to the depth of its rituals, festivals, and history.

Before committing to the decision to convert to Judaism, there are a lot of questions one must ask. One of the first and, depending on the potential convert, most important will be: How long does it take? There is no standard but, according to one of the rabbis I worked with in New York, it requires at least one year. But why so long? It's in order for the person converting to experience the full cycle of the Jewish year.

What is the Jewish year? Well, this is a pretty substantial topic by itself. So, I'm going to skim over the general organization, then focus on where we are right now because we are coming up on the New Year (Rosh Hashanah), the Day of Atonement (Yom Kippur), and Sukkot (the harvest festival). It is the most important part of the Jewish year, and there is much to be done to prepare.

But, I digress. Back to the big picture. The months of the Jewish calendar are based on the cycles of the moon, so they do not sync with the Gregorian (or Western/Christian) calendar. The months, including important festivals, are as follows:

- Tishrei: Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur, Sukkot, Sh'mini Atzeret, Simchat Torah;

- Cheshvan

- Kislev: Hanukkah

- Tevet

- Sh'vat: Tu B'Shvat (new year for trees)

- Adar: Purim - there can also be an Adar 2, depending on the moon cycle

- Nisan: Pesach, Yom HaShoah

- Iyar: Yom Ha'Atzmaut, Yom HaZikaron

- Sivan: Shavuot

- Tammuz: Fast of Tammuz

- Av: Tisha B'Av, Tu B'Av

- Elul: The Month of Reflection and Preparation (Cheshbon HaNefesh)

We are currently in the month of Av. In the list above, I included some important holidays that I will discuss in more detail below. They are the Fast of Tammuz, Tisha B'Av, and Tu B'Av. The period that begins with the Fast of Tammuz and ends with Tisha B'Av is known as The Three Weeks.

From Michael Strassfeld's "The Jewish Holidays"

The Three weeks are a period of mourning. It begins and ends with a day of fasting. Historically, many of the most significant offenses committed against the Israelites/Jews occurred during this period. Primary among them: The destruction of both Temples, first by the Babylonians and then by the Romans; the expulsion from England in 1290; and the expulsion from Spain and Portugal in 1492.

As I wrote previously, in the time between Pesach and Shavuot, we count the Omer. There are echoes of the themes of the counting of the Omer in The Three Weeks. We move from birth to death. From destruction to rebuilding and renewal. We sacrifice and celebrate.

During The Three Weeks, Tisha B'Av in particular is a solemn holiday. It's like a minor version of Yom Kippur. During the first nine days of Av (The Nine Days), we are supposed to eschew the consumption of meat and wine, except on Shabbat. It was interesting to me that we entered Av as I had been contemplating the role of meat in my diet. To a certain extent, not eating meat makes ritual observance easier. Before beginning the fast for Tisha B'Av, observers usually eat a light meal typical of those in mourning - hard-boiled eggs, fruit, vegetables.

On Tisha B'Av, we read from the Book of Lamentations, known as "Eichah" in Hebrew, meaning "How" or "Alas". Its authorship is generally attributed to Jeremiah, a prophet who prophesied the demise of the Kingdom of Judah. Eichah is comprised of five poems about the destruction of the city of Jerusalem and the Temple. The liturgy takes on a different character for the holiday, one that is more somber and plaintive. The destruction of the second Temple marked the end of temple service, the end of Jewish sovereignty, and the beginning of the Exile - "galut" in Hebrew - that, arguably, continues today. There is some debate about the necessity of this holiday after the establishment of the State of Israel, but that is another, much larger conversation.

Of note, many people yearn for the construction of the third Temple in Jerusalem, which would be on the Temple Mount (the location of the al-Aqsa Mosque and Dome of the Rock, a very important holy site in Islam). Liberal Jews mourn the loss of the Temple without wanting it to be rebuilt. We recognize the flaws in the world and our duty to repair it; however, we also understand that the Temple is no longer central to that process.

After Tisha B'Av, we celebrate Tu B'Av, the 15th of Av. Shabbat Nachamu, which we just observed on August 1, begins the cycle of seven weeks of comfort leading up to the renewal of Rosh Hashanah (the "head of the year"). The month of Elul, which follows Av and precedes Tishrei, is known as the period of "Cheshbon HaNefesh", or accounting of the soul.

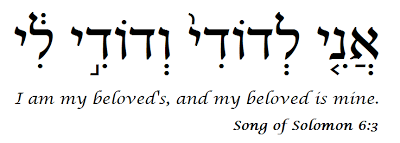

Elul embodies the process of courtship between us and God. On Shabbat, we welcome the Sabbath Queen - the "Shechinah" or divine presence that dwells among us. Some people believe that the name "Elul" refers to the well-known phrase from the Song of Solomon:

During this time, we prepare for the High Holy Days, when we ask God to include us in the Book of Life for the coming year. We do this every year.

And this brings us back to the centrality of cycles in Jewish life. The Jewish holidays, specifically, fit together into a coherent whole that ebbs and flows through the seasons. The holidays themselves relate to nature, history, and our inner spiritual lives. They connect us to each other, and to God through the very essence of Creation. In the words of Arthur Waskow, in his book "Seasons of Joy", "[The holidays are] intended to teach us how to experience more fully the profound patterns of the world."

Long ago, it was believed that celebrating in and engaging in the cycle would help it continue. This would create a spiral that would culminate in the arrival of Messiah. Modern liberal Judaism generally rejects the idea of Messiah. But we can still see the importance of the holidays in that they honor the Unity that underlies all life. The Shema, the defining statement of Judaism, proclaims the unity of Creation:

The name "Yisrael", or Israel, means "to wrestle with God," and is a description of the relationship between God and the Jewish people. As Arthur Waskow writes: "What is wrestling? It is a close grappling that has some elements of fighting and some elements of embracing in it, at the same time and in the same process." It is our responsibility as Jews to wrestle with the past and the present.

In my journey, I am constantly confronted by new experiences and new ideas. Things that challenge my notions of Judaism, the importance of ritual, of observance, and how those things connect with me personally. Understanding the importance of cycles in Judaism helps a great deal. Waskow writes: "If we read and think about the text, perhaps we will uncover [deeper] meaning, or create it for ourselves in a way that helps us live and grow."

Historically, Jewish students have participated in "shylah" and "teshuvah", or question and response. The modern Jewish Renewal movement is centered on the notion that the historical process of Torah is Torah; that is to say, that there are layers to the law that reveal themselves over time and in different contexts. This is both inspiring and encouraging to me. One of the reasons I have felt so welcome within Judaism is that it is a living religion. It changes with time, and adapts.

Cycles have been very important in my conversion experience. I started when I was 14 or 15, and over the years my interest in converting to Judaism has come and gone , but never left. It is a constant that challenges me to engage, to question, to grow. Although that may imply that when I do stand before the Beit Din it will be the end of something, in reality, it will only be the beginning of a lifetime of learning, growing, and passionate devotion.

Thank you.